In Luanda, Portuguese taxi drivers wouldn’t take you wherever you want if you were Black…

Luanda, November 1968. It’s a heavy rainy day in the Angolan capital. It’s 5pm on the main square downtown when Nzinga, a young Angolan renamed António by the colonial administration, hails a taxi. He jumps at the back, and the old mini-van with deflated tyres and broken suspensions leaves the square along the asphalt road. João, the Portuguese taxi driver, asks where his client wants to be driven : the musseque of Sambizanga. The driver immediately brakes, arguing that the sandy track is too damaged because of the heavy rain that has been falling on Luanda for the last three days. The young client insists, anxious to join his girlfriend and impress her with his arriving in a taxi, yet old and battered. The wheels laboriously hit the road again, until touching the sandy track that leads to the musseque, but stops just in front of the large lagoon made of the constant rainwater. For the taxi driver, there’s no way his tyres touch the water. A few cars cross the mud puddles, but most of the people – all Angolan – join their houses by crossing bare-footed, the water reaching their thighs. Senhor João orders the young António to clear out his car and to end his journey by swimming until joining his “slum”. “I am a taxi driver, not a boatman!”

In 1968, Angola was living its last years under the Portuguese colonial domination – that started in the 16th century – and had been waging a war for independence for the 7 previous years, since the first popular insurrection attacks in 1961, by the MPLA, and soon the FNLA and UNITA. In Luanda, the country’s capital, while the Portuguese settlers and the African assimilated people (“assimilados” who speak Portuguese and eat with a knife and a fork) occupied the city centre (“baixa”), the African population was living mostly inside the musseques – a kimbundu word (“mu seke”) meaning “the red sand”.

These slums located at the outskirts of the city were made of frail houses erected on the red sandy soil where 300 000 people lived together – half the city’s population at the time. They were both a bottomless pit of social misery, and a stronghold for the anti-colonial resistance. Its winding and narrow streets (only one person at a time could walk in these) prevented easy access to the Portuguese colonist, and provided enough room to build a strong local identity and a revolutionary culture. Even the taxi drivers – most often Portuguese people – did not dare to enter the musseques, both out of fear and out of social and ethnic discrimination.

BEHIND THE HUMOROUS LYRICS – “I’M A TAXI DRIVER, NOT A BOATMAN!” – HERE IS A STINGING CRITICISM OF THE COLONIAL POWER AT THE TIME.

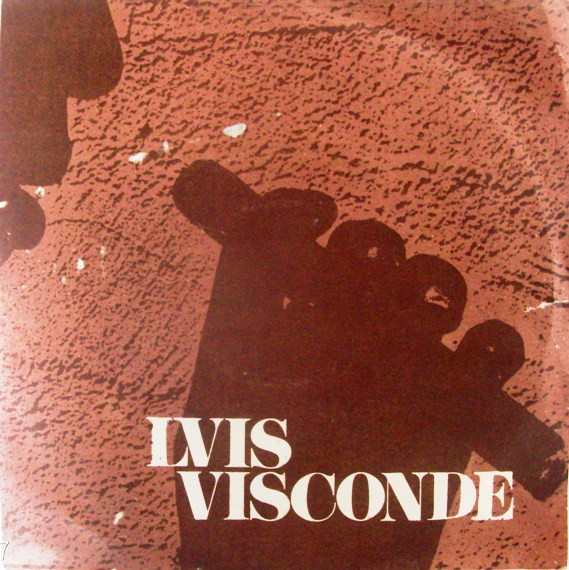

This is the sad story told by Luis Visconde (sometimes spelt Luiz) in “Chofer de Praça” (“Taxi Driver”, in Angolan Portuguese language). Behind the humorous lyrics – “I’m a taxi driver, not a boatman!” – here is a stinging criticism of the colonial power at the time. Stinging, because the slightest anti-government opinion was forbidden and immediately repressed. Stinging, because whilst most of the protest songs were generally sung in one of the local languages (kimbundu) so they could go unnoticed by the censorship of the local power police (the “bufos”) and the Portuguese State political police (the PIDE), Luis Visconde used the colonist’s Portuguese language to denounce the ghettoisation of the African population in the musseques. It contains a hint of social irony, through the different uses of language between the narrator and the taxi driver : the former speaks a perfect Portuguese, with delicate words, while the latter – a settler – uses a very oral and slang form of it. Here was a way for Luis Visconde to show that the stigmatised Angolan population had a proper education.

This song is one of the most emblematic of all Angola’s protest songs. Six years later in 1974, once Angola would gain independency, thus one could think the taxi drivers would no more be reluctant to drive to the musseques. Maybe, only if it wasn’t for the immediate 18-year long brutal civil war the country would wage, and the inertness of the political power who until today in 2016, has not resolved the major rainwater flooding issues that occur almost everyday during the rainy season, on the road to the musseques.

Personally, “Chofer de Praça” is one of the very first afro-lusophone songs I ever heard upon settling in Lisbon, via the essential compilation Soul Of Angola – Anthologie De La Musique Angolaise 1965/1975.

Lyrics – English translation

[by Marissa J. Moorman in Intonations: A Social History of Music and Nation in Luanda, Angola, from 1945 to Recent Times]

I hailed a car from the plaza [taxi]

Anxious to see my honey

The chauffeur then complained

When I told him my honey lived in the suburbs

“Rainy season in the suburbs, I won’t go

I am a taxi driver, not a boatman”

So I implored

“I am asking you, Mr taxi driver, please take me

It’s not her fault she lives in the suburbs,

And rain is the work of the nature”

Then the chauffeur, overcome by me,

Hit the gaz, crossing the mud puddles

When I looked at my watch and asked him

To glue the accelerator to the floor

The chauffeur, annoyed, responded

“If you want to see your love

Cross the mud puddles on foot

I won’t ruin my car

Just so you can show off!”

Original lyrics

Mandei parar um carro de praça,

ansioso em ver meu amor.

Chofer de praça então reclamou

quando eu lhe disse que meu bem morava no subúrbio:

“Tempo chuvoso no subúrbio não vou,

pois sou chofer de praça e não barqueiro!”

Então implorei:

“Peço senhor chofer, leve-me por favor.

Ela não tem culpa de morar no subúrbio.

Quanto à chuva, é obra da natureza.”

Então chofer, dominado por mim,

na borracha puxou, atravessando lagoa,

quando eu olhei pro relógio

e pedindo que colasse o acelerador ao tapete.

Então chofer trombudo respondeu:

“Se você quer ver seu amor, atravesse a lagoa a pé!

Não vou partir o meu popó só porque você quer dar show!”

Luis Visconde “Chofer de praça”

Musseque Chicala – view from the Fort © Célia Macedo, 2011

Musseque Chicala – view from the Fort © Célia Macedo, 2011

Cover picture credit : Lusa